Alsharq Tribune- Ahmed Essam

The start of the Muslim holy fasting month has always been a time of great festivity in Egypt, for both rulers and the ruled.

On the evening of 28 February, the Dar Al-Iftaa in Cairo announced the conclusion of Shaaban, the eighth month of the Muslim lunar calendar. This meant that 1 March would be the first day of Ramadan, one of the holiest days for Muslims who observe a fast during the holy month from dawn to dusk for 29 or 30 days until the start of the 10th month of the Muslim calendar, Shawal, which marks the start of Eid Al-Fitr, the festival that ends the month of Ramadan.

Shortly after the eishah [evening] prayers, the announcement was made on Egyptian Radio and Television. It was followed by traditional Ramadan songs that welcome the advent of the Muslim holy fasting month, including the iconic Ramadan Gana (Ramadan is upon us) by Mohamed Abdel-Motaleb and Aho Geih ya Welad (Here it comes everyone) by Al-Tholathi Al-Mareh, both of which date from the mid-20th century. Special radio and TV channels then started special programming.

Meanwhile, the beginning of the taraweeh prayers, extended evening prayers, was being broadcast on social media and some private channels. These last for the 29 evenings of the holy month.

Al-Hussein Mosque opposite Al-Azhar Mosque in Islamic Cairo is one of the mosques that the pious attend for the taraweeh prayers. Near this mosque, like around every main mosque in Cairo and other governorates, evening festivities last until the pre-dawn hours, with the first Sohour (last meal before dawn) in particular being marked in the older restaurants of the historic quarters of the city.

Earlier on Friday, Sufi orders in Egypt organised a march to mark the beginning of the holy month. With hundreds joining, the march was headed by chair Abdel-Hadi Helal and accompanied by Osama Al-Azhari, the minister of Waqf. It went across the older quarters of Cairo, starting at the Mosque of Sidi Saleh Al-Gaafari and heading towards Al-Hussein Mosque. Al-Azhari had already inspected the central mosques in other cities, with his deputies doing the same in governorates across the country to make sure that preparations for a month of extended prayers were all set.

According to Abdel-Azim Fahmi, founder of Sirat Al-Qahira (Biography of Cairo), an independent initiative that works on documenting the heritage of the capital, festivities to welcome Ramadan have always been deeply rooted in the history of the city, especially after the start of the Fatimid Dynasty’s rule of Egypt in the 10th century and throughout the subsequent period of Mameluke rule that lasted until the 16th century. Before and after these centuries, he said, welcoming Ramadan was observed with less attention even if not in lesser fashion.

Fahmi said that the lavish festivities associated with the advent of Ramadan were first introduced by the Fatimids, who had a taste for grandeur. A frequently cited anecdote refers to the Fatimid Caliph Al-Hakim Bi Amr Allah, the sixth Fatimid ruler of Egypt, who ordered the manufacture of a silver cover for the pulpit of Al-Azhar Mosque in the month of Ramadan as a sign of rejoicing.

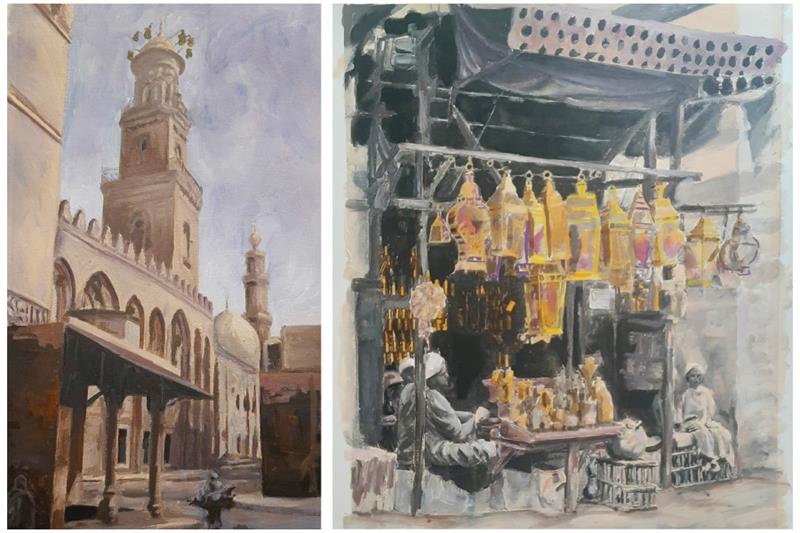

“The imprint of the Fatimids on the festivities of Ramadan was very large. However, given that there is very little left of the Fatimid architecture of Cairo in the city today, the oldest site that still survives is the minaret of the Mosque of Qalawan, where the crescent moon of Ramadan used to be looked for to mark the beginning of the month,” he said.

Built for a Mameluke Sultan, Al-Mansour Qalawan, who ruled Egypt in the second half of the 13th century, the Qalawan Complex of a mosque, madrassa, and mausoleum still stands in Al-Muiz li-Din Allah Street in Islamic Cairo today. Religious and judicial figures would ascend the staircase of the minaret, and if they agreed that the crescent moon could be seen, they would then come down to announce the beginning of the fasting month.

“This would be a very big moment, with the minaret of Qalawan itself lit with hanging lanterns and with many more lanterns and candles being lit in every mosque across the city,” Fahmi said

BEGINNING RAMADAN: Lanterns and candles would also be lit in the stores that were scattered across the street, which by the time of the Mamelukes was named Al-Kassaba Al-Ozmah. A march headed by leading religious and judiciary figures and joined by leading merchants would proceed to the residence of the Sultan to wish him well on the occasion, Fahmi added.

As the march proceeded across the city, onlookers would come to the windows of their houses to watch and join the jubilant mood. Once the Sultan had received the delegates and accepted their greetings, he would order generous donations of food to be offered both to the rich and the poor.

This would be followed by long sessions of prayers in the city’s mosques, food shopping across the city, and the appearance of the messaharati, a man who would walk around the city before dawn during Ramadan banging a drum and calling on people to wake up for Sohour.

According to Fahmi, the festivities of the month were a sign of the grandeur that marked the Fatimid but especially the Mameluke rule of Egypt. They were a sort of political statement, rather like the grand mosques, madrassas, and mausoleums that were built during the rule of the Mamelukes. The march at the beginning of the month was a statement of the power of the ruler, who would at times be present to oversee the distribution of food and other gifts.

In his book on Sultan Qalawan, published by the Cairo publishers Madbouli as part of its Pages from the History of Egypt series, historian Mohamed Hamza notes that the behaviour of the Sultans was an integral part of their status as rulers at the top of Egypt’s mediaeval political system.

According to Hamza, the grandeur that marked Qalawan’s 11-year rule was only part of the wider context of economic prosperity and political stability that marked his reign.

“Egypt was prosperous and flourishing under the rule of Qalawan,” Hamza wrote. Its prosperity could be seen everywhere, and unfair taxes were removed and the government reformed to make it more efficient in preventing injustices. Education, agriculture, trade, and charity were all prosperous under Qalawan, according to Hamza. “The country’s health services were particularly impressive,” he wrote.

Fahmi said that a clear sign of this prosperity was the fact that during the month of Ramadan the lanterns on the minarets and city façades would be lit from sunset to dawn, “so that people would know that the time was still right for them to eat and drink.”

“Once the lanterns were extinguished, they would know that it was time for them to start observing the fast.”

During the evening hours in Ramadan, children would be doing what they still do today, especially in the older quarters of the city — playing with coloured lanterns in their hands. “Much of what we see today in terms of celebrating the advent of Ramadan dates back to the Fatimid and Mameluke periods,” Fahmi said. Such traditions were never fully suspended, not even during the Ayoubid Dynasty between the Fatimids and Mamelukes or during later Ottoman rule when Egypt was no longer the seat of an empire.

Fahmi said that during the time of Egypt’s former ruling Mohamed Ali family, starting from its founder in the early years of the 19th century up until the last years of the rule of Egypt’s last monarch king Farouk, there was always keen attention paid to the advent of Ramadan. Things were obviously different from the way they had been done in the Middle Ages, but all the ruling members of the Mohamed Ali family realised the significance of the holy month of Ramadan and made sure that they did what the public expected of them.

From the first night and throughout the holy month, the rulers of Egypt in the 19th and 20th centuries made sure that they did what their predecessors had done to mark the beginning of Ramadan, offering and accepting greetings for the beginning of the month, holding Quranic recitations, giving money to charity, and joining public Iftars (meals for breaking the fast).

Ramadan, Fahmi said, was always also a political matter. “This is precisely why Napoleon made sure that he showed respect for the traditions of the month” during his time in Egypt at the head of the French Expedition to the country in the late 18th century.

However, things changed dramatically after the beginning of the rule of the Free Officers in Egypt after the 1952 Revolution. “The idea of a ruler and subordinates was off the table. Under the republic, the president saw the people as citizens and not subordinates,” Fahmi said. During the rule of successive presidents since then, every president has given due attention to the beginning of the month of Ramadan and to made sure that people have affordable access to commodities.

According to Mohamed Afifi, a professor at Cairo University, the rulers of modern and contemporary Egypt have always known how to position their religious observances, “each in a different way and to a different extent, but always with a political objective as well.”

Observing prayers, especially on Fridays in the larger public mosques, has been another custom that every ruler has committed to during the Muslim holy month, Afifi said. In this respect, there has been no difference between the Mameluke Sultans and the modern presidents of Egypt, he concluded.

.png?locale=en)